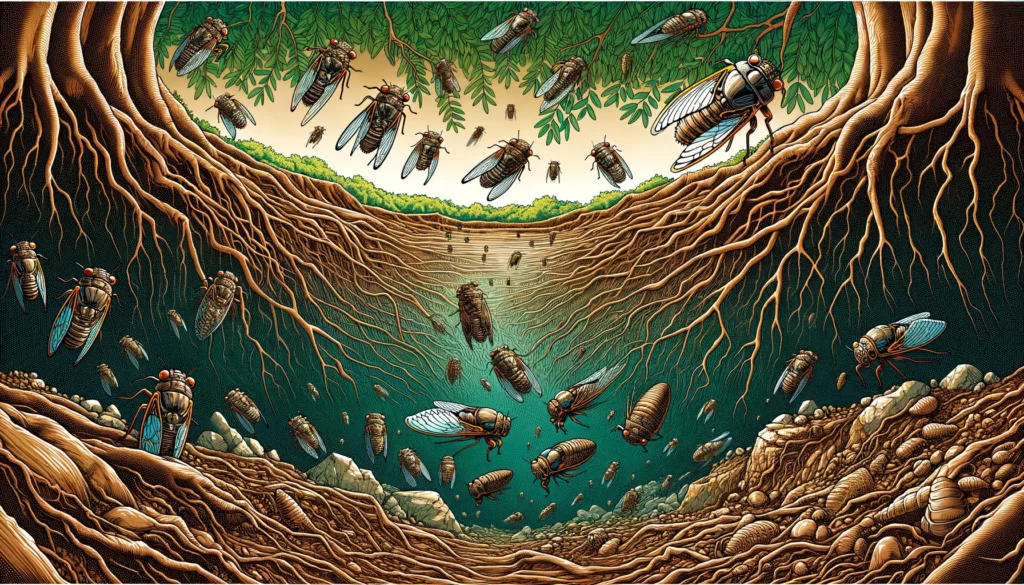

Periodical cicadas spend most of their time underground as nymphs. Then, every 13 or 17 years, an entire brood of billions and billions of cicadas emerges. The insects storm out all at once, fulfilling one of the most bizarre lifecycles in nature. But why do they do it, and how do they know when to do it?

Why cicadas have this strange cycle

Nature often works with year-long cycles, where many organisms are tuned to the seasonal changes of the environment. Migration is a good example of this. Some predators also have natural cycles that recur every 2 or 3 years. So, cicadas, which are virtually defenseless against most predators, found a way to make use of these cycles. They deviate from all norms and emerge at prime-numbered life cycles of 13 or 17 years.

These cycles are not only unusually long but also effectively desynchronize them from the cycles of potential predators and competitors. This basically means no predator species can adapt to their cycles.

The cicadas have another ace up their sleeve, though it’s not a very elegant one. To ensure enough of them end up surviving, they simply overwhelm with numbers. That’s why cicadas come out in such great numbers at such odd times: so they can avoid predators and make sure enough of them survive — the predators can’t eat them all.

But how do these creatures, which spend most of their life underground, know when it’s time to emerge en masse? The answer involves a complex interplay of biology, environmental cues, and an intrinsic biological clock.

How cicadas know when to come out

We should mention that not all cicadas are periodical. There are over 3,000 cicada species, and only some of them are periodical — the others have “normal” yearly cycles.

Researchers have spent a long time trying to figure out how exactly cicadas synchronize themselves. While it’s still not entirely clear, it’s probably linked to environmental cues and a molecular clock. Dr. Chris Simon, molecular systematist at the University of Connecticut’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology told Entomology Today:

“The year of cicada emergence is cued by what I and others believe to be an internal molecular clock,” she said. “The clock is most likely calibrated by environmental cues that signify the passage of a year, such as the trees leafing out, changing the composition of the xylem fluid on which they feed. The molecular clock keeps track of the passage of years. The accumulation of 13 or 17 years triggers the emergence of fifth instar nymphs. The day of emergence is triggered by accumulated ground temperature. This was demonstrated by James Heath in a study published in 1968.”

Basically, what the study concluded was that the cicadas use their internal clock to know what year it is. This is possibly linked to tree cycles as well, which change their chemistry slightly based on yearly cycles. Then, when the year is right, they follow thermal cues to know when the season is right.

This is also tied into the cicadas’ moulting cycles. They have five moulting cycles, the fifth one being the one they emerge at. To sum it up, cicadas know when to come out thanks to two main factors:

- Biological Clocks and Counting: Cicadas have an internal biological clock that appears to help them keep track of passing years. Studies suggest that cicadas count the cycles of the trees’ sap flow, which diminishes annually during winter.

- Temperature: The final year of their cycle brings a crucial cue: temperature. Soil temperature needs to reach about 64 degrees Fahrenheit (approximately 18 degrees Celsius), which typically occurs in spring. This temperature threshold triggers the final developmental changes in the nymphs, prompting them to emerge synchronously when conditions are ideal for survival on the surface.

2024’s emergence

The year 2024 is a special one for cicadas. Not one, but two major broods are making an appearance this year, Brood XIII and Brood XIX.

This is all the more exciting because they are not the same type of cicadas. Brood XIII cicadas stay underground for 17 years, while Brood XIX stay underground for 13 years. The last time that both broods came out at the same time was in 1803.

Even though billions of cicadas are expected to come out in a relatively short period of time, you shouldn’t really be worried. Cicadas are not dangerous for humans and they’re not really dangerous for your pets, either — unless they eat a lot of them, in which case they can have digestion problems.

Even for most plants, cicadas don’t do any damage. They are not locusts, contrary to popular belief, and the only damage they do to plants is when they lay their eggs in small scratches on the plants. So, if you live in a cicada area and want to be extra safe, you can temporarily close your windows and cover your plants to be extra safe.

Overall, the cicada emergence is a spectacle of nature — one of the strange phenomena that make nature so impressive and surprising — not something to be feared.