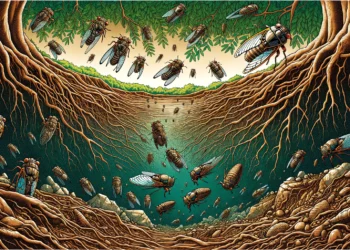

Periodical cicadas are some of the most intriguing insects in the world. These cicadas emerge from their underground slumber like clockwork every 13 or 17 years, depending on their brood. When the time is ripe, millions of cicadas flood nearby forests and farms across the midwestern and eastern United States.

This year is quite special. Both a 13-year brood and a 17-year brood will emerge simultaneously, particularly around the Illinois area. A “brood” is the scientific term for a group of cicadas that emerge synchronously.

Just how loud is it?

The first thing you’ll notice if a cicada swarm is closing in is the noise. Periodical cicadas (genus Magicicada) are among the loudest insects in the world. They produce noise over 100 decibels at close range, or about as loud as a rock concert or car racing event. Any louder and the human ear could suffer damage. According to researchers at Johns Hopkins, the cicada’s high-pitched buzzing sound could worsen tinnitus. The sound has been described as standing right next to a spinning food blender at max rev or a gas-powered lawn mower.

Is cicada noise that dangerous? In 2021, the CDC’s NIOSH Noise and Bio-Acoustics Team conducted field experiments with professional decibel monitors to dispel some myths and set the record straight. They reported that the level of cicada noise measured 3 feet from a heavily infested tree may indeed approach 100 dBA. However, the noise level will be substantially lower if you are standing farther away (e.g., 94 dBA at 6 feet, 88 dBA at 12 feet, 82 dBA at 24 feet).

“It is true that noise exposures at or above 85 A-weighted decibels (85 dBA) are considered hazardous to hearing. However, safe noise exposure limits are established assuming repeated exposures over long periods of time. The NIOSH REL has been set to prevent hearing loss from noise at work over 8-hour workdays, 40-hour work weeks, and a 40-year working lifetime.”

“Although it takes repeated exposures of sufficient duration to cause hearing loss, NIOSH recommends that preventive measures be used any time the noise is 85 dBA or higher. . . regardless of duration. This is not because the sound is immediately dangerous to hearing, it is because you don’t always know how long the sound will last or what other noise exposures you might accumulate over time. In addition, susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss varies across individuals, and we can’t know whether a particular person is highly susceptible to noise effects until after it is too late. What’s more, noise is associated with problems other than hearing loss, such as stress and hypertension3 and tinnitus. Imagine hearing a sound like cicadas—all day, every day—even while you try to sleep… for some people that is the reality of tinnitus. Reducing noise levels can help prevent these other unwanted effects of noise. Remember this: If the noise level exceeds 85 dBA (use the NIOSH SLM app to check), it’s always a good practice to move away or wear some hearing protection,” the researchers wrote.

The cicada song

For the cicadas, this high-pitched tune is no simple noise at all. Rather, it’s a vital part of their survival strategy, meant to identify one another and find mates.

The cicada shrill is known as chorusing. It’s produced solely by male cicadas vibrating their tymbals, a noise-emitting organ on the side of their abdomen. Each male cicada has a pair of tymbals, which they flex by contracting internal muscles, producing a loud pop as the tymbals buckle. The sound is amplified by the insect’s hollow abdomen which acts as a resonance chamber. Relaxing these muscles returns the tymbals to their original position, ready for the next sound wave. This rapid-fire contraction and relaxation produces the cicada’s distinctive loud song.

Females lack tymblas, so they don’t make noise. They have abdomens filled with organs and tissues for egg production and oviposition.

The volume and pitch of these calls serve a dual purpose. Primarily, they are mating calls, with each species singing a unique tune to attract females of their kind. This specificity prevents cross-species breeding and supports diverse cicada populations. However, not all aspects of their song’s purpose are fully understood by scientists, adding an element of mystery to these noisy creatures. Cicadas will also shrill in times of distress, such as when they feel threatened by another animal.

A Natural Defense Mechanism

Beyond love songs, cicadas use their powerful voices for protection. Singing mainly during the warmest parts of the day, their chorus can repel birds. The intensity of the cicada’s song sounds awful to birds (and most humans I might add) and disrupts their communication, making it challenging for them to hunt effectively. By synchronizing their calls, cicadas in the same brood amplify their collective volume, further enhancing their defense against avian predators.

As for the cicadas themselves, they have their own ‘earmuffs’ to shield them from their powerful emissions. The insects have a set of tympana — mirror-like membranes that function as ears — that can temporarily disable their hearing to prevent damage while singing.

How the sound affects us

Although the cicada song is a vital part of their unusual lives, let’s face it: the noise can be deeply annoying. In fact, they may even affect your cognitive performance (unless you like their distinct shrill). In a 2021 study, researchers at the Indiana University Bloomington investigated how the loud noises produced by Brood X cicadas, which can reach up to 100 decibels, affect human cognitive functions.

This particular brood resurfaces every 17 years and has been heard across nearly every county in Indiana. The experiment involved participants completing the Montreal Cognitive Assessment both under quiet conditions and amidst the cacophony of cicadas. Participants were divided based on their affinity for cicada sounds, the idea being that those who enjoyed the noise might perform better in its presence. Results indicated that participants who disliked cicada sounds scored slightly lower in noisy conditions, while those who liked the sounds showed no significant change in their performance, though their scores tended to be slightly higher.

The findings suggest a statistically significant impact on cognitive functions, particularly in memory recall, which took longer under cicada noise conditions.

Luckily, cicada swarming only happens every 13 or 17 years in a given area. When they emerge, you can expect the ‘concert’ to last 1-2 weeks, depending on the species’ life span.

The life of a cicada is one of acoustic marvel and biological ingenuity. As researchers continue to unravel the complexities of these creatures, each discovery adds a new layer of understanding to how life thrives through adaptation and innovation. Their ability to coexist through specialized calls is a testament to the intricate dance of nature’s evolutionary forces.