In the warm summer days of Japan, cicadas reign as the ambient soundtrack—clicking, chirping, and rattling like tiny engines. But wander near the woods around the University of Tsukuba and you might hear something less organic. A familiar melody—Pachelbel’s Canon—emerging not from speakers, but from the bodies of insects themselves.

Naoto Nishida, a biologist now at the University of Tokyo, has done something gently surreal: he has turned cicadas into living instruments. By threading electrodes into the membranes they use to sing, he and his colleagues have transformed them into the world’s most unusual MIDI players—cyborg bugs, chirping out concertos.

Hijacking the Hum

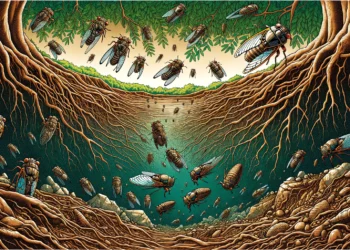

Male cicadas produce their iconic and very loud sound using a pair of drum-like organs called tymbals. These ridged membranes, tucked just beneath the sides of their abdomen, buckle in and out when a specialized muscle flexes, producing a click. Rapidly repeated—hundreds of times per second—the clicks form a continuous, resonant chirp. Their hollow abdomens amplify the noise like the body of a violin.

Using this natural mechanism, the Japanese research team implanted electrodes into the tymbals of Graptopsaltria nigrofuscata, a large brown species common across Japan. This particular species was chosen for its anatomy: large body size, and relatively few muscles near the tymbals, making surgical precision easier.

Once connected to a computer interface and amplifier, the insects became the world’s strangest MIDI players. Different voltages triggered different pitches. Some bugs could hit a low A at 27.5 hertz; others chirped their way to a high C at 261.6 hertz. Over time, the researchers coaxed the insects into producing tones that spanned more than three octaves—comparable to the range of a glockenspiel.

Then came the real test. With the bugs hooked up and calibrated, the team fed them the notes of Pachelbel’s Canon. It worked.

“It’s the most offensive rendition we’ve ever heard,” wrote Futurism. Which is a valid point. But the achievement wasn’t musical perfection—it was biological control. This could be important when it comes to creating insect cyborgs.

Emergency! Sound the Cicadas!

Cyborg insects may sound like science fiction, but they’re part of a growing field with serious goals. Since the 1990s, scientists have experimented with turning insects into biohybrid robots. In 2015, researchers at Texas A&M steered cockroaches using tiny electrode backpacks. In 2021, scientists in Singapore guided Madagascar hissing cockroaches through simulated disaster zones using computer-linked electrodes.

These tiny cyborgs are resilient, energy-efficient, and capable of navigating tight, complex spaces. That makes them attractive candidates for search-and-rescue operations, environmental monitoring—and now, potentially, emergency broadcasting.

The cicada experiments, described in a preprint on arXiv, open new possibilities. “Cyborg insects could be used in emergency situations such as earthquakes,” the researchers suggest in their paper. The idea: lightweight, flying insects could relay alert sounds even in collapsed buildings or disaster zones where power is limited and infrastructure is damaged.

They wouldn’t need speakers or batteries—just a little electricity and their own built-in chirping organs.

Despite the eerie overtones, the cicadas fared reasonably well. Nishida emphasized that the procedures were minimally invasive and that “some of them were like, ‘OK, use my abdomen.’” A few were even released back into the wild.

Still, not everyone will find the idea of surgically enhanced insects easy to swallow. The imagery—creatures pulsing with electricity, chirping out wedding tunes in a lab—feels like something out of a dystopian novella. But in a world increasingly shaped by both climate chaos and technological ingenuity, hybrid solutions may soon chirp louder than fiction.

Would you want a symphony of bugs playing your emergency alert?