Researchers from the Aarhus University, the Copenhagen Zoo (both in Denmark) and Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, report that the mutation rate of humans has been slowing down over the past million years or so. Today, it’s much slower than that of our primate relatives. The finding is important as mutation rate is one of the yardsticks by which we estimate when humans as a species first appeared. It could also help us better protect large primates in the wild.

Deviations from the norm

Fewer new mutations occur per year in today’s humans than in our closest primate relatives, the study reports. The team sequenced the genomes of whole families (mother, father, and offspring) of chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans, looking at how many new mutations younger generations have compared to their elders. They then compared them with corresponding data from humans.

“Over the past six years, several large studies have done this for humans, so we have extensive knowledge about the number of new mutations that occur in humans every year,” says lead author Søren Besenbacher from Aarhus University.

“Until now, however, there have not been any good estimates of mutation rates in our closest primate relatives.”

Ten different families (seven of chimpanzees, two of gorillas, and one of

This higher rate would have an impact on the length of time estimated to have passed since humans and chimpanzees (our closest genetic relatives) speciated into distinct lineages. That’s because we estimate this time by looking at how different their genomes are from ours: a higher mutation rate would mean that differences accumulate over a shorter period of time, which would throw our estimations of the last common ancestor off.

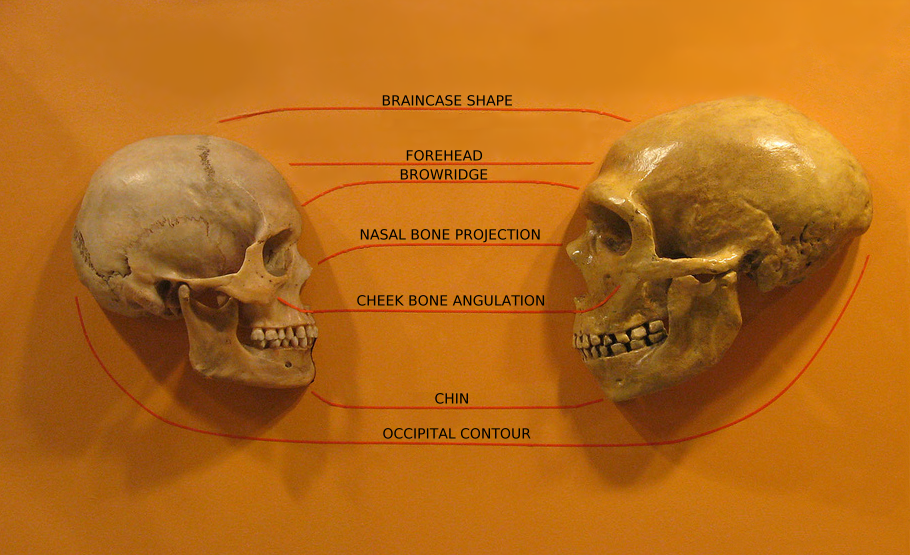

Image credits Fred Spoor via ScienceMag.

For example, if we apply the average mutation rate measured in humans (which we did up to now), human speciation/differentiation from chimps should have occurred around 10 million years ago. If we apply the new mutation rates the team presents, however, speciation should have taken place around 6.6 million years ago, the team writes.

“The times of speciation we can now calculate on the basis of the new rate fit in much better with the speciation times we would expect from the dated fossils of human ancestors that we know of,” explains co-author Mikkel Heide Schierup from Aarhus University.

The findings would also impact our estimate of when Neanderthals and modern humans split, too. Judging by the team’s findings, it should be closer to the present than we assumed (based on the same mechanism we’ve talked about with chimps, with some caveats).

Image via Wikimedia.

But that’s all about the past. The findings also have implications for the future, the team argues — especially in regards to great ape conservation.

“All species of great apes are endangered in the wild. With more accurate dating of how populations have changed in relation to climate over time, we can get a picture of how species could cope with future climate change,” says

study co-author Christina Hvilsom from Copenhagen Zoo.

The paper “Direct estimation of mutations in great apes reconciles phylogenetic dating” has been published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.