Hammerhead sharks are the strange-looking ones. They look like someone grabbed their skull by the eye sockets and stretched their heads out sideways, while the rest of their bodies look like those of a normal shark.

You might wonder – what are the advantages of having a hammer-shaped head? And how did hammerhead sharks get that way in the first place?

I’m a scientist who has been studying sharks for almost 30 years. The answers to some of these questions have surprised even me.

Benefits of the hammer

Scientists think sharks with hammer-shaped heads have three main advantages.

The first has to do with eyesight. If your eyes were pointing in two opposite directions, say, by your ears, it would give you a much wider field of vision. Each eye would see a different part of the world, so you’d have a better sense of what was around you. But it would be hard to tell how far away things are.

To make up for that trade-off, hammerhead sharks have special sense organs, called ampullae of Lorenzini, scattered on the underside of their hammer. These porelike organs can detect electricity.

The pores basically act like a metal detector, sensing and locating prey buried under sand on the ocean floor. Regular sharks have these sensory organs too, but hammerheads have more. The farther apart these sensory organs are on a hammerhead’s stretched-out head, the more accurate they are at pinpointing the location of food.

And finally, scientists think hammers help sharks make quicker turns while swimming. If you’ve ever walked in gusty wind with an umbrella or flown on an airplane, you know how powerful large surfaces can be in motion. If you’re a hammerhead shark, and your intended dinner swims by quickly, you can turn more rapidly to catch it than other fish can.

The hammerhead family tree

It would be nice if scientists like me could look at fossils and trace the development of hammerhead sharks over time. Unfortunately, fossils of hammerhead sharks are almost entirely of their teeth. That’s because the bodies of sharks do not have bones. Instead they’re made of cartilage, which is what your ears and nose are made of. Cartilage breaks down much more quickly than teeth or bones do, so it rarely gets fossilized. And tooth fossils don’t tell us anything about the evolution of hammerhead skulls.

Nine different kinds of hammerhead sharks swim in the oceans today. They vary both in size and in the shapes of their heads. Some have very wide heads relative to their bodies. These include the winghead shark (E. blochii), the great hammerhead (S. mokarran), the smooth hammerhead (S. zygaena), the scalloped hammerhead (S. lewini) and the Carolina hammerhead (S. gilberti).

Others have smaller hammers relative to their bodies, including the bonnethead (S. tiburo), scoophead shark (S. media), small-eye hammerhead (S. tudes) and scalloped bonnethead (S. corona).

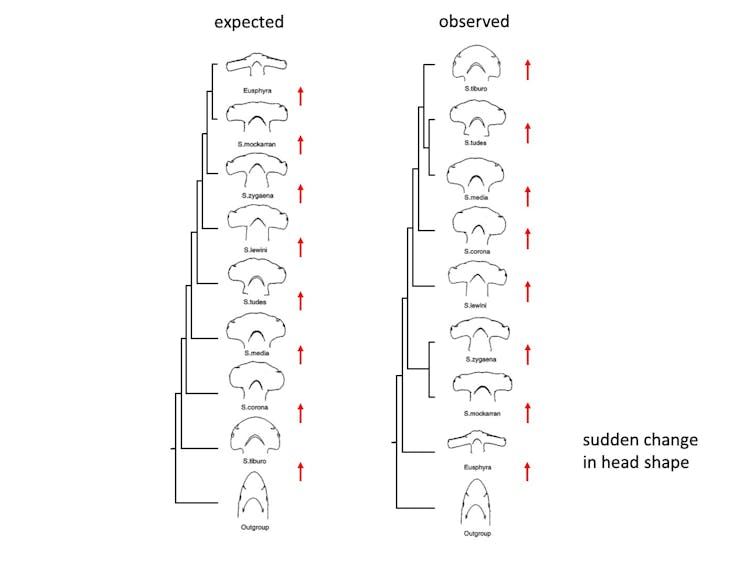

Scientists long assumed the first hammerhead sharks did not have much of a hammer but, over time, some slowly evolved bigger hammers. We thought the different hammerhead sharks living today were snapshots from different periods in the evolutionary process – with the small hammerheads being the oldest species on the family tree and the huge hammerheads being the newest ones on the scene.

Since we don’t have fossils to look at, scientists like me have explored this idea using DNA. DNA is the genetic material found in cells that carries information about how a living thing will look and function. It can also be used to see how living things are related.

We took DNA from eight of the nine hammerhead species and used it to look at the relationships among them. The results were not what we expected at all. The older species had the proportionally bigger hammers and the younger species had the smaller hammers.

Deformities as assets

When scientists think about evolution, we usually assume that living things change a little bit at a time, slowly fine-tuning themselves to take better advantage of their environment. This process is called natural selection. But that’s not always the way it works, as hammerhead evolution shows.

Sometimes an animal can be born with a genetic defect that turns out to be really useful for its survival. So long as the abnormality is survivable and the animal is able to mate, that trait can be passed down. We think that’s exactly what happened with hammerhead sharks.

The hammerhead species that branched off the earliest is the winghead shark (E. blochii), which has one of the widest heads. Over time natural selection has actually shrunk the size of the hammer. It turns out the most recent hammerhead species is the bonnethead shark (S. tiburo), which has the smallest hammer of all.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Gavin Naylor, Director of Florida Program for Shark Research, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.