A team of scientists from Cambridge University have developed a vaccine that works against the common elements of all coronaviruses. The vaccine, which has only been tested on mice so far, promises to protect us from existing strains, as well as ones that haven’t emerged yet.

“Our focus is to create a vaccine that will protect us against the next coronavirus pandemic, and have it ready before the pandemic has even started,” said Rory Hills, a graduate researcher in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Pharmacology and first author of the report.

“We’ve created a vaccine that provides protection against a broad range of different coronaviruses – including ones we don’t even know about yet,” he added.

A pandemic that changed the world

Few people had ‘global pandemic‘ on their 2020 Bingo card — let alone one caused by a coronavirus. Yet the year kicked off with a dreadful disease that would end up bringing society to a halt for months. In fact, it was only when we developed vaccines that we were finally able to supress the new coronavirus.

The SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were developed with unprecedented speed, surpassing even the most optimistic predictions. But it still took around a year, a year in which many lives were lost, and society took a big hit. Researchers now know we can react quickly to diseases, but they want something more: they want to be proactive.

The problem is that most viruses that can cause epidemics are new viruses that mutate, often from animals. So how do you protect yourself from a virus that hasn’t evolved yet?

This is where the new vaccine comes in.

A multi-target vaccine

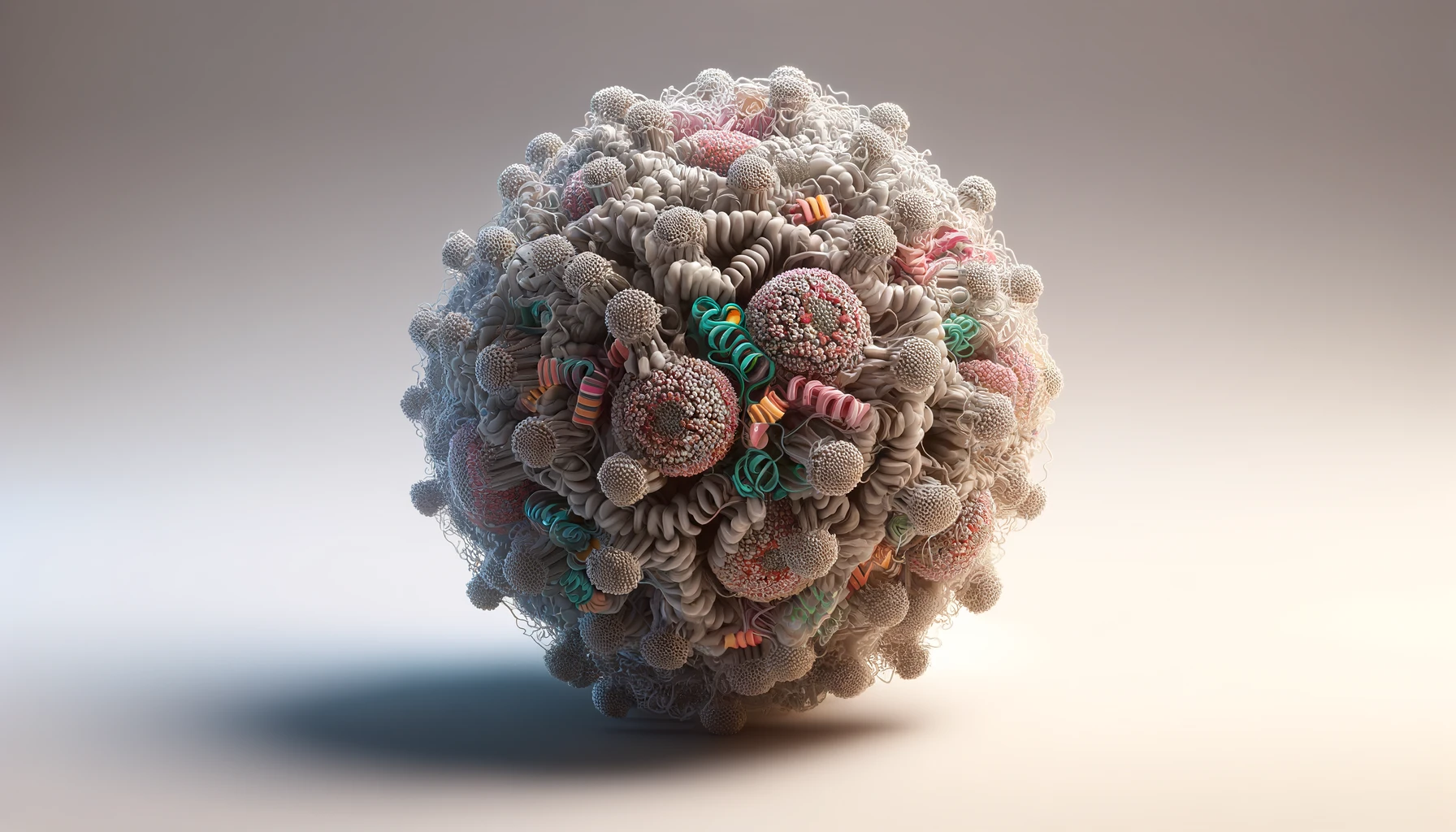

The so-called “Quartet Nanocage” vaccine works with a “ball” of proteins bound together. This ball also contains numerous chains of different viral antigens that target features shared by many coronaviruses.

“We don’t have to wait for new coronaviruses to emerge. We know enough about coronaviruses, and different immune responses to them, that we can get going with building protective vaccines against unknown coronaviruses now,” said Professor Mark Howarth in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Pharmacology, senior author of the report.

Testing the vaccine on mice seemed to trigger a broad immune response that should protect against multiple coronaviruses. Although there’s still a long way to go from mice to humans, the vaccine design is simpler than other candidates in development. This should bring it into clinical trials faster.

The project improves on previous work by Oxford and Caltech groups. These groups were also involved in the present research, joined by a team from Cambridge. The new vaccine should enter Phase 1 clinical trials in early 2025, researchers say, but there are few guarantees in this type of project.

Overall, this new vaccine is part of a strategy of proactive vaccination. This involves developing vaccines before disease outbreaks, rather than reacting to them once they occur. The idea is to build immunity within a population before they are exposed to a virus or bacteria. With this, we may finally be able to reduce the impact of infectious diseases.

Proactive vaccination against diseases

Proactive vaccination is especially critical in managing diseases with pandemic potential. It prepares communities and healthcare systems to handle infections more effectively, thereby saving lives and reducing healthcare costs. In the past few decades, we’ve grown complacent against infectious diseases. But, as the novel coronavirus pandemic showed, all it takes is one pathogen to cause a global disaster.

Howarth mentions:

“Scientists did a great job in quickly producing an extremely effective COVID vaccine during the last pandemic, but the world still had a massive crisis with a huge number of deaths. We need to work out how we can do even better than that in the future, and a powerful component of that is starting to build the vaccines in advance.”

However, despite its promise, proactive vaccination also comes with big challenges. In addition to the vaccines themselves, there are no procedures on how something like this would be used. For instance, one option would be to administer them in populations where new coronaviruses are most likely to emerge (for instance around bat populations). Another would be to deliver it as a COVID-19 booster in vulnerable people, with the benefit of protecting against other coronaviruses.

But what researchers really hope is that countries will also stockpile these vaccines and have them ready for when a dangerous new pathogen emerges. We’re still a ways off from that objective, but researchers are slowly inching closer. Hopefully, when the next pandemic-potential pathogen emerges, we’ll be prepared. Because it will come.

The study was published in Nature Nanotechnology.

Was this helpful?