We’ve talked in-depth about who the best chess player is and why that’s so hard to estimate (there really is no clear conclusion when comparing players from different years). To make that all even more complicated, it seems that in addition to all the difficulties that make comparisons so challenging, there are also stylistic or psychological effects. Some chess players may have a “superstar” aura around them that makes their opponents play differently than normal.

In a new study, two US researchers looked at this superstar effect and found significant consequences. Their findings could shed new light on who the best chess players in history really are, but also help us better understand psychological relations that are not only present in chess (and competitive games, in general), but also in the work environment.

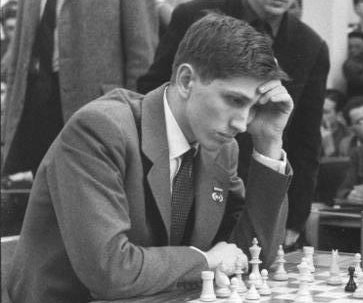

The legendary chess player Bobby Fischer once said “I don’t believe in psychology — I believe in good moves.” Fischer would go on to become world champion in 1972 by taking on the ‘chess machinery’ of the USSR, practically destroying all opposition he encountered along the way. Although Fischer’s domination was relatively short (he withdrew from top chess after disagreements with the chess federation), he is still regarded as one of the best (if not the best) chess players in history. At the time, Fischer was almost universally feared at the board, with former world champion Boris Spassky declaring: “When you play against Bobby [Fischer], it is not a question of whether you win or lose. It is a question of whether you survive.”

This psychological effects of chess superstars like Fischer are well known and widely debated — not just in the world of chess, but also in other sports and at the workplace. Leading companies often try to hire (or even poach) “superstar employees”, but it’s not clear if this has a positive or negative effect on the company as a whole (and on other employees).

The study, led by Eren Bilen, focused on chess because this centuries-old game offers advantageous ways of eliminating confounding factors and unwanted influences.

For starters, chess is a game of complete knowledge — both players see the board in its entirety and know what is happening. It’s also a game in which both players play with the same pieces that do the same thing, and the only difference is that one moves first, while the other moves second.

In addition, because computer algorithms are so much better than humans at chess by now, they can also be used to analyze games (and individual moves) and see not only who played better, but also which games were more complex.

“We are lucky that we are able to use the help of neural-networks to get at this interesting question,” Bilen told ZME Science in an email. “With such networks, we are able to estimate how “complex” or “creative” a given chess game was. For example, if players only follow theory and exchange all their pieces at any given opportunity and the game ends in a draw in say 15 moves, the network would identify this game as a non-complex game.”

The team found that the superstar effect is always negative — at least directly. In other words, when other players play superstars, they always seem to perform worse than they normally would. However, the indirect effect can sometimes be positive; when performing at events where superstars are also performing, other players can perform better than they usually do — but only if the superstar isn’t very dominant.

The chess superstars

When it comes to the ultimate chess superstars (the best players in history), it’s impossible to be completely objective, but a few names usually pop up. The three most common ones to come up are Fischer, Garry Kasparov, and Magnus Carlsen (the current world champion).

The three have different arguments to support their claim to the “greatest ever” title. Fischer dominated the chess world with an authority that has not been seen before or since but only for a few years. Kasparov was on top for about two decades, while Carlsen is currently the undisputed champion for almost a decade, but against a field of unprecedented strength.

To look at these games in more depth, the researchers also looked at the complexity of the games and how “nettlesome”, or difficult to play against these superstars are. According to the study, it’s Fischer who takes the crown here.

“The most complex games we saw were with Fischer, followed by Kasparov. In other words, we are able verify that if you play against Fischer, you will definitely be facing a very complicated game, potentially full of tactics, and he will outperform you with his better technique. Same thing with Kasparov,” Bilen explains.

“Of course, you might ask: Is it Fischer who initiates the “nettlesomeness” or is it the other player? The answer is, it is a combination of the two. We know for certain that if you are the higher rated player (as in Fischer’s, Kasparov’s or Carlsen’s case) you have an incentive to make the games more complicated so that you can show how much more skilled you are compared to your opponent. For example, if you keep exchanging pieces and have a boring game, then the game would probably end in a draw as there wouldn’t be enough pieces left on the board to give you an edge. So the superstar player definitely wants to make games more complex, and the other player doesn’t really get much of a say in this. Note that you cannot force a draw against a stronger opponent, which most players nowadays would want against Carlsen as they would be gaining rating points.”

Why this matters

While the study adds more fuel to the “who’s the best chess player ever” debate, it’s unlikely to actually settle the debate. It’s interesting to see how these great champions performed, but the practical utility of the study lies elsewhere.

The indirect superstar effect seems to depend on the skill gap between the superstar and the competition. In other words, if the champion was too dominant, too good compared to the opposition, this led everyone but the superstar to perform worse and make more mistakes. Presumably, psychological pressure is at work. But when the gap was small and the challengers felt like they had a chance, they actually tended to perform better than usual.

What this means for companies looking to sign “superstar” employees is that if the skill gap between the superstar and the rest of the cohort is small, it could be a motivator and encourage everyone to perform better. But if the gap is too high, the opposite could happen. Of course, whether or not the findings apply to the workplace is still not entirely clear.

“The takeaway for firms seeking to hire a superstar employee is that hiring a superstar employee may create a positive or an adverse effect on the cohort’s performance depending on the skill level gap. If the gap is too large, there may be negative side effects of hiring a superstar employee. In these settings, a highly skilled team member would destroy competition and create an adverse effect on the rest of the team members,” the study concludes.