In early 1994 “going online” often meant fighting the family for phone‑line supremacy, listening to a 28.8‑kilobit modem shriek, and settling for text‑heavy bulletin boards or AOL chat rooms.

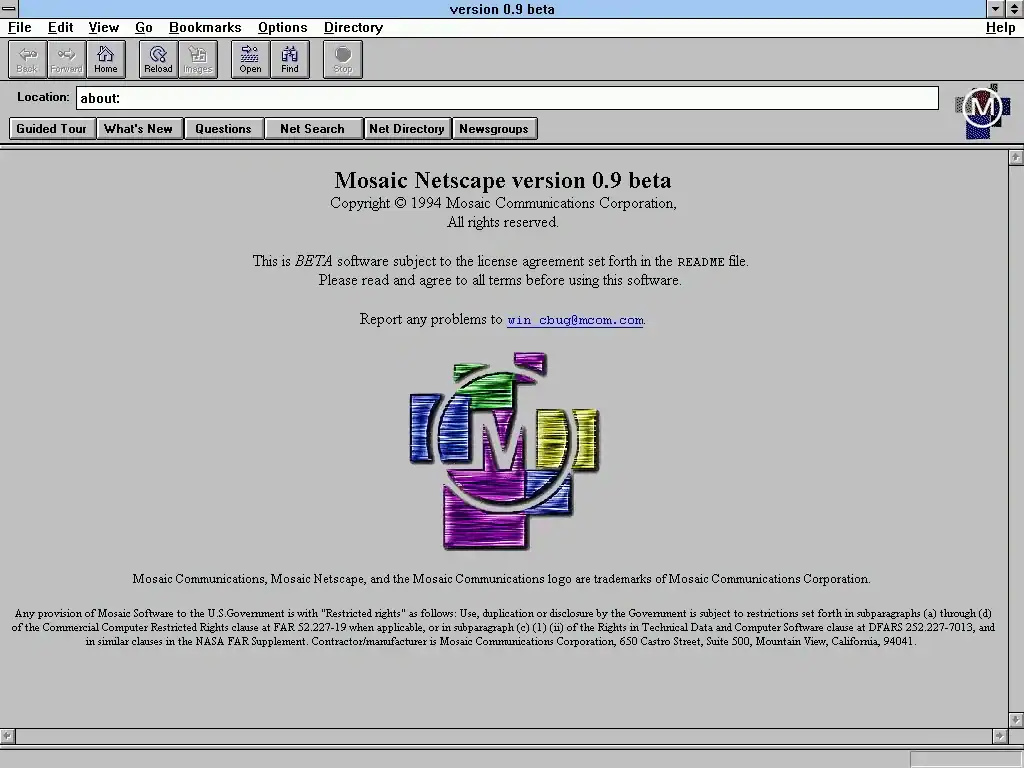

However, on a December evening that year, a teal‑and‑purple compass bearing a single “N” appeared on thousands of PC desktops—and the internet went Technicolor. The program behind that compass was Mosaic Netscape 0.9, which was rebadged a few weeks later as Netscape Navigator.

It didn’t invent the Web, but it yanked off the training wheels. Within two years, the little “N” would become the unofficial gateway to cyberspace and the spark that ignited the first great dot‑com fever dream.

How a Teal Compass Icon Kicked Off the First Dot Com Boom

Navigator’s unlikely journey began on April 4, 1994 in a drab Mountain View office where Mosaic Communications Corporation hung its hastily painted sign. Its founders were a 22‑year‑old University of Illinois grad named Marc Andreessen, fresh off creating the original NCSA Mosaic browser, and Jim Clark, the billionaire who had just left Silicon Graphics.

As legend has it, Andreessen and Clark originally conceived an idea for an online gaming service for the Nintendo 64 console. Don’t feel bad if you haven’t heard of it, because it never came to fruition. Nintendo demurred, the project didn’t happen, and the two entrepreneurs suddenly found themselves facing a small, inconvenient detail: they had a plethora of talented people with nowhere to build.

What they settled upon instead was something called Mosaic Netscape 0.9—essentially a brand-new web browser unlike anything before it. This all ended in a trademark kerfuffle with the University of Illinois, which claimed copyright to the term “Mosaic”, resulting in the company’s rebranding to Netscape Communications Corporation in November 1994. By 1995, the browser was known simply as Netscape Navigator.

That first test build, released free on October 13, stunned users with lightning page loads and inline images. Within four months, it had seized more than three‑quarters of global browser traffic. The browser, now formally Navigator 1.0, became the de facto definition of “the internet” for millions who were discovering the Web at school, work, or the corner cybercafé.

Wall Street caught the fever almost as quickly. On August 9, 1995, Netscape went public at a last-minute‑doubled price of $28 a share. Frenzied trading drove it to $75 before closing at $58.25, valuing the 16‑month‑old company at $2.9 billion. Analysts coined the phrase “Netscape moment” to describe the kind of initial public offering (IPO) that proves a whole new industry is real. Venture capital suddenly hunted for browser clones the way prospectors once chased gold dust, and a generation of garage coders typed business plans under the glow of Netscape’s marquee.

Netscape Ruled the Internet in the 90s Then Microsoft Played Dirty

Success carried a side effect: it painted a target on Navigator’s back. Just weeks before the IPO, Microsoft shipped Internet Explorer 1.0—a clunky re‑brand of licensed Mosaic code but bundled free with Windows 95.

Microsoft’s distribution muscle meant every new PC already arrived with a browser, erasing the retail advantage that once belonged to Netscape’s $39 corporate licenses. Rumors later surfaced of a 1995 meeting where Microsoft allegedly proposed carving up the browser market—Netscape would stay off Windows while IE would ignore Mac and Unix. Whether or not the offer was real, Netscape refused to yield, and the browser war began in earnest.

Internet Explorer was decidedly subpar in the beginning. But Bill Gates kept updating at breakneck speed: version 2.0 gave way to 3.0, then 4.0, each more menacing and decidedly cheaper than the last. Cheaper in that it was free—bundled with Windows, which, it must be said, was in most homes, offices, and schools.

Inside Netscape’s airy “bubble cube” offices, engineers churned out innovations that still scaffold today’s Web. In May 1995 Brendan Eich wrote JavaScript in 10 caffeine‑fueled days, giving static pages their first programmable life. Lou Montulli devised the HTTPcookie, making shopping carts and persistent log‑ins possible. Netscape’s cryptography team rolled out Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) so that credit‑card numbers could travel the net without fear.

Yet the same rapid‑fire culture bred what employees jokingly called featuritis. Each new widget sat atop hurried patches, and Navigator’s once‑sleek codebase ballooned into a labyrinth. Shipping schedules slipped, bugs multiplied, and rival demos of IE no longer felt embarrassingly sluggish.

By late 1997, the cracks were visible. Netscape posted its first quarterly loss and executed its first layoff in its short history. Hoping to regain momentum, CEO Jim Barksdale bet on a radical move: on January 22, 1998 Netscape announced it would open‑source its browser under the newly formed Mozilla Project and stop charging for Navigator altogether.

Thousands of volunteer programmers cheered—but management simultaneously chose to throw out Navigator’s aging code and start over with a pristine rendering engine called Gecko. Software essayist Joel Spolsky later blasted the rewrite as “the single worst strategic mistake” a company could make, because it sidelined Netscape during the crucial years when Microsoft was tightening its grip. Navigator 5 never reached the launchpad; Navigator 6 limped out two years late, already overshadowed by IE 5 and the newly released IE 6.

Just as morale wavered, dial‑up juggernaut America Online (AOL) of “you’ve got mail” fame, swooped in. On November, 24, 1998, AOL agreed to buy Netscape for $4.2 billion in stock; market exuberance pushed the closing‑day value near $10 billion by March 1999. Some Netscape veterans cashed out gleefully, while others fretted that AOL’s service‑provider mindset would smother the hacker culture they cherished. One of Navigator’s earliest architects, Jamie Zawinski, quit on day one, publishing a scorching blog post predicting doom.

AOL tried wringing value from its purchase. It paired with Sun Microsystems to launch the Sun‑Netscape Alliance (later iPlanet), selling enterprise email and directory servers built on Netscape code. It re‑skinned the browser as Netscape 7 and plugged it into the AOL portal.

However, none of those moves halted Navigator’s decline; IE claimed more than 90 percent of the market by 2002. In July 2003 the newly merged AOL Time Warner dismantled what remained of Netscape’s R&D and laid off large swaths of staff, though it donated $2 million to spin the volunteer Mozilla team into an independent Mozilla Foundation.

That foundation finally harvested the open‑source seeds Netscape had planted. After stripping Gecko to its essentials, developers released Phoenix, then Firebird, and finally, in November 2004, Mozilla Firefox 1.0. Lightweight, standards‑respecting, and armed with tabbed browsing and pop‑up blocking, Firefox clawed back double‑digit market share from Internet Explorer and reignited competition. In a twist of irony, Netscape’s most enduring triumph came under a different name.

Netscape, the brand, however, limped along on nostalgia. AOL issued Netscape 8 in 2005—an awkward hybrid that allowed users to switch between IE’s Trident engine and Gecko—followed by Netscape 9 in 2007, a decent Firefox fork that gained little traction. On December 28, 2007 AOL announced the end: Navigator development would cease, and support would expire on March 1, 2008 after one final patch labeled 9.0.0.6. Fourteen frenetic years after its first download prompt, the browser that popularized the Web was history.

From Internet Hero to Historic Footnote

Why did such a rocket plummet so quickly? The most obvious external factor was Microsoft’s bundling strategy: by giving Internet Explorer away with the world’s dominant operating system, Redmond starved Netscape of sales and visibility. Even when Navigator remained technically superior, many users saw no reason to hunt for a separate installer over a slow modem. Internally, featuritis and the decision to trash the old codebase hamstrung Netscape’s engineering cadence; while IE shipped brisk upgrades, Netscape vanished into years‑long rewrites. Strategic drift compounded the pain. What began as a singular quest—“the best browser on Earth”—ballooned into portals, groupware, and e‑commerce suites that diluted focus right when the core product needed emergency triage.

Yet to view Netscape only as a cautionary tale misses its colossal imprint. Every time a drop‑down menu springs to life via JavaScript, a cookie remembers your cart, or a padlock flashes beside an HTTPS address, you are touching Netscape DNA. Navigator’s decision to embrace open standards—and later open source—helped ensure that no single company could ever own the Web outright. Firefox, Chrome, Safari, Edge: all owe a debt to that one audacious moment when a commercial giant said, “Here’s our code—have at it.”

Even the brand ekes out an afterlife. Verizon, heir to the AOL legacy, still offers a cut‑rate Netscape dial‑up plan for corners of rural America where broadband remains a mirage. Somewhere out there, on a dusty Windows XP tower, a customer may still double‑click an icon with a swirling silver N and watch the constellation animate: “Netscape is now loading…” For the rest of us, the legacy is subtler but far more pervasive—embedded in the very grammar of the modern internet.

Had Navigator not erupted when it did, the Web’s path to mainstream might have wound more slowly. Instead, a clutch of twenty-somethings turned a campus prototype into a shipping product in six months, rocketed it onto Wall Street in sixteen, and fired up a global gold rush whose aftershocks still jolt Silicon Valley. Netscape rose like a comet and burned out just as fast, but the light it cast changed the horizon forever. When you next glide from a cooking blog to a cat GIF in two clicks, spare a grateful nod to the big teal compass that first pointed the way.