Over 50 years ago, researchers circumnavigated the Americas sampling ocean life along the way at regular intervals. In the process, they discovered a striking relationship: the abundance of most marine species is linked to their body size such that their collective mass winds up being the same. Krill are a billion times smaller than tuna, but their numbers are a billion times more abundant. If you were to weigh all the krill in the ocean, the mass should be close to all the tuna — but not anymore.

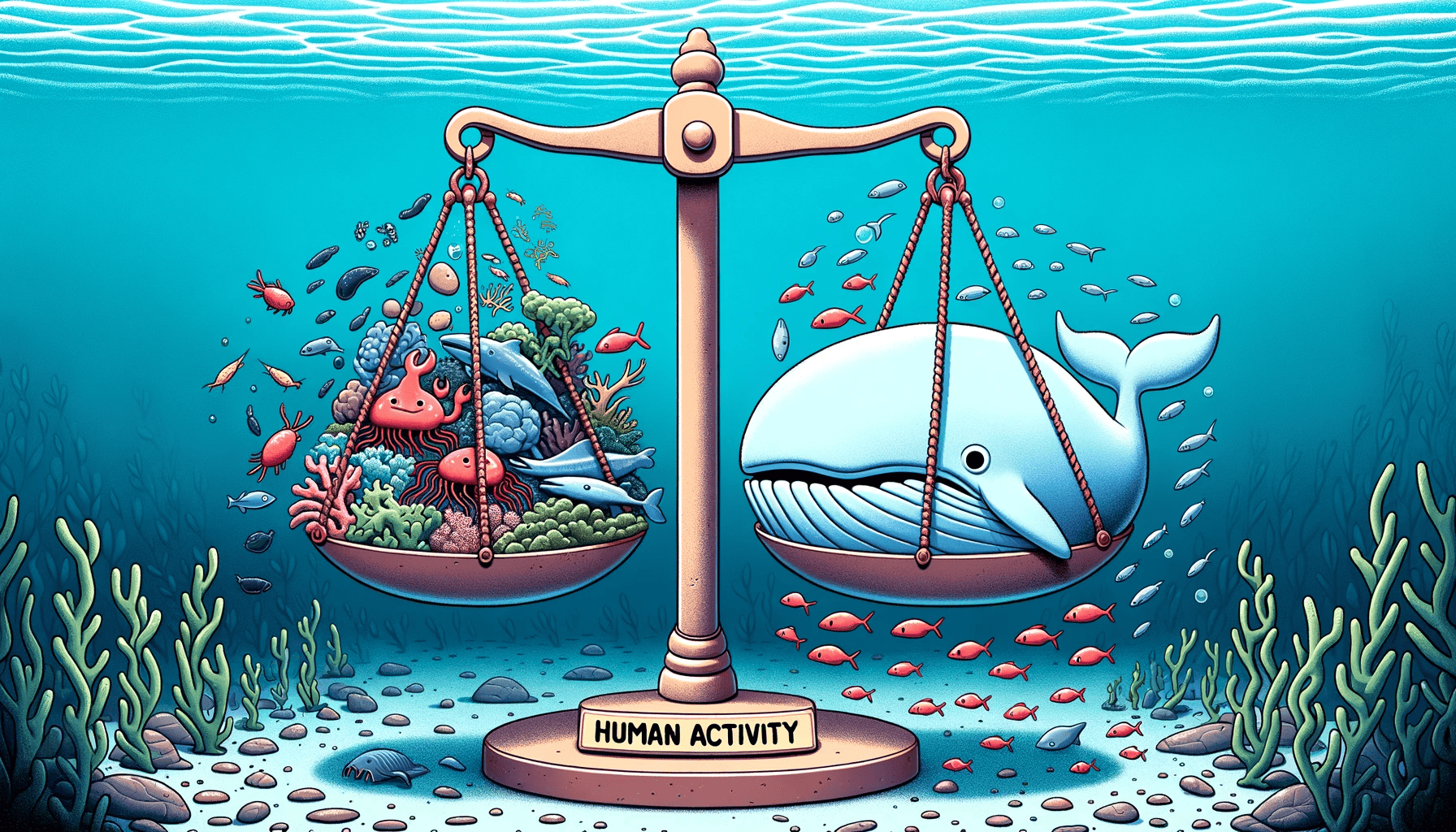

A new study found that human activity like industrial fishing has broken this mathematical relationship known as the Sheldon spectrum, after Ray Sheldon, a marine ecologist who first reported this relationship in 1969.

Humans are at it again

The Sheldon spectrum — the total mass of a marine population stays the same even as the individual size changes — applies to virtually all ocean life, from the tiniest bacteria to the largest whales. Even though a whale is trillions of trillions of times larger than a bacterium, its population size is smaller by the same order of magnitude, so their mass evens out.

“It kind of suggests that no size is better than any other size,” Eric Galbraith, a professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at McGill University in Montreal, told Wired. “Everybody has the same size cells. And basically, for a cell, it doesn’t really matter what body size you’re in, you just kind of tend to do the same thing.”

But Galbraith was shocked to find that the Sheldon spectrum has been broken, specifically for larger marine creatures. Generally, the larger the fish or crustacean, the easier it is to catch. Global fisheries are notoriously unsustainable, with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) pointing out that one-third of fish stock worldwide is experiencing depletion due to “overfishing and habitat destruction.”

Galbraith and colleagues, led by Max Planck Institute ecologist Ian Hatton, used modern satellite imagery and recent in situ ocean measurements to estimate the abundance of plankton and fish. They also used a reliable estimate of marine mammal populations from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the organization that designates threatened or endangered species.

“One of the biggest challenges to comparing organisms spanning bacteria to whales is the enormous differences in scale,” says Hatton.

“The ratio of their masses is equivalent to that between a human being and the entire Earth. We estimated organisms at the small end of the scale from more than 200,000 water samples collected globally, but larger marine life required completely different methods.”

These estimates were compared to those from 1850, which they modeled using records of fish and marine mammals that industrialized fishing and whaling had captured.

In these pre-1850 levels, the Sheldon spectrum held across the board, with biomass staying remarkably consistent across size brackets. But when they compared these numbers to modern-day biomass, the relationship broke down in the upper one-third of the spectrum where the largest marine life can be found.

“Humans have impacted the ocean in a more dramatic fashion than merely capturing fish,” explained marine ecologist Ryan Heneghan from the Queensland University of Technology.

“It seems that we have broken the size spectrum – one of the largest power law distributions known in nature.”

Since 1800, the researchers found that the very largest size bracket of marine life experienced a reduction in biomass of nearly 90%. For instance, all whale species declined from more than 2.5 million to under 800,000 from 1890 to 2001.

In other words, a law of nature that has seemingly been true for eons has now been broken in just 100 years thanks to human activity. And overfishing isn’t the only problem we’ve brought upon ocean life. Climate-induced changes in the ocean are causing additional stress, throwing the ocean into a health crisis, which includes a loss of biodiversity.

More research is needed to understand how this huge loss in biomass affects the oceans, but it can’t be anything good. Having healthy fish stock is critical to the overall functioning of ocean ecosystems, as well as certain planetary functions. For instance, the ocean is known to play an indispensable role in regulating carbon in the atmosphere.

Meanwhile, we already know the solution: reduce overfishing. Fish compose less than 3% of the annual human food consumption, so cutting back on fish shouldn’t be that big of a deal. But that’s of course easier said than done.

The findings appeared in the journal Science Advances.